Tunisian President Kaïs Saïed (right) and then–Prime Minister Hichem Mechichi. (Photo: Tunisian Presidency)

Tunisian President Kais Saied abruptly suspended Parliament on July 25, removed cabinet ministers including the minister of defense, assumed executive power over the judiciary, and deployed the military to enforce his rule. The military subsequently prevented elected members of parliament from meeting. Parliament, for its part, has characterized Saied’s actions as unconstitutional. Democracy advocates, both domestic and international, have called Saied’s actions a coup.

To gain more perspective on Tunisia’s rapidly unfolding and poorly understood crisis, the Africa Center has asked its North Africa expert, Dr. Anouar Boukhars, to share his insights.

What’s behind the governance crisis in Tunisia?

“Saied … has complained bitterly of being hamstrung by Tunisia’s political system and its constitutional rules that limit his powers.”

The governance crisis that has seen President Kais Saied grab power is the culmination of months of institutional gridlock and political infighting. This has largely pitted the President against Prime Minister Hichem Mechichi and the Speaker of Parliament Rached Ghannouchi over the powers of the legislature and the respective roles of the dual executive—the president and the prime minister. Since he won a landslide victory in the presidential run-off contest in 2019, Saied, a political independent known for his disdain of party politics, has complained bitterly of being hamstrung by Tunisia’s political system and its constitutional rules that limit his powers to the realms of the military and foreign policy. Since he did not run under a political party, Saied has lacked support in Parliament to advance his agenda.

Under Tunisia’s dual executive system, the prime minister is the head of government directing the cabinet. The authorities of the prime minister were strengthened following Tunisia’s move to democracy in 2011 in response to the over-concentration of power by the longtime autocratic President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali. The prime minister is typically appointed by the president as the nominee from the party with a parliamentary majority. For nearly 2 years, Saied has locked horns with two prime ministers, Elyes Fakhfakh and Hichem Mechichi, whom Saied himself selected, after the deeply fractured Parliament proved unable to rally behind a consensus candidate.

Former Prime Minister Hichem Mechichi.

(Photo: ILO)

The most damaging feud pitted Saied against Mechichi, supported by a slim parliamentary majority comprised of three parties—Ennahda, Karama Coalition, and Qalb Tounes. Saied and Mechichi contested over who had the responsibility to appoint ministers and oversee the security services. The tug-of-war escalated in mid-January 2021 when the prime minister unveiled a cabinet reshuffle that Parliament had approved but Saied denounced as unconstitutional. Since then, Tunisia has remained politically deadlocked and its government in limbo. This blockage and paralysis unfolded amid rising anger among Tunisians over pandemic disruptions and the deteriorating state of an economy that has contracted nearly 10 percent since the pandemic following the sharp drop in tourism.

The most recent and devastating wave of COVID-19 infections and deaths was the last straw that ignited protests among a public increasingly fed up with squabbling politicians and dysfunctional institutions. It also provided Saied, who has cast himself as Tunisia’s savior from institutional paralysis, political corruption, and economic stagnation, the opportunity to impose a new political status quo through invoking emergency powers that some of his advisors had envisaged months ago.

What does the Tunisian Constitution say about the powers of a president to dismiss the prime minister and suspend parliament?

Article 80 of Tunisia’s 2014 Constitution allows the president to take exceptional measures for 30 days “in the event of an imminent danger threatening the homeland’s integrity or the country’s security and its independence, in a way that results in the impossibility of carrying on with the normal functioning of state institutions.” Saied argues that he had no choice but to unlock a political crisis that, he contends, has brought Tunisia to the brink of economic and public health collapse.

“Article 80 … mandates that a number of conditions must be met before and after emergency measures are invoked. … None of these conditions have been met.”

Article 80, however, mandates that a number of conditions must be met before and after emergency measures are invoked, including the requirement that the president consults the prime minister and speaker of the parliament, and that parliament remains in session throughout the interim period of emergency. None of these conditions have been met even if Saied and his supporters adamantly maintain that the president acted within the bounds of his constitutional powers.

Unfortunately, a constitutional court that could have reviewed the president’s decision to declare and even potentially prolong the exceptional measures he claimed under Article 80 of the Constitution has never been formed despite the Constitution mandating its establishment. Tunisia’s political parties took a long time to agree upon nonpartisan appointments to the Constitutional Court. When Parliament finally passed a bill to create the Court in April 2021, Saied refused to ratify it.

Why is this crisis so significant for Tunisia and the region?

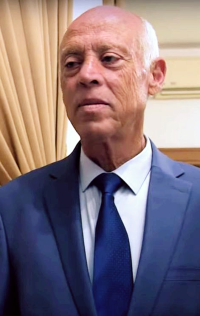

Tunisian President Kaïs Saïed.

(Photo: Nawaat)

Saied’s power grab is an alarming development that puts the only democracy in the Arab world at risk of unraveling. Under the most optimistic scenario, Saied’s move is a provisional power play that allows him to regain the political advantage, impose his ministers, and enact his preferred policies. The second scenario is what some observers fear is the beginning of an authoritarian process marked by a return to the personalization of power and presidentialization of politics. This authoritarian temptation and its seductive lure for some Tunisians disgruntled with political infighting and poor governance is a common reflex in many crisis situations. This path rarely ever ends well, however, as seen in a number of countries that slid back into brutal despotic rule or devastating civil strife.

Tunisians may still weather this political storm and pull their country back from the brink, as they did during the last consequential political crisis in late 2013. Then, key political leaders, unions, and civil society actors successfully sought compromise to defuse tensions and keep the country on its democratic course. Now, Saied is promising to protect Tunisian democracy even as he maneuvers to empower the presidency. The moderate Islamist party Ennahda has also taken a more conciliatory approach, calling for holding another dialogue and, importantly, withdrawing calls for protests.

A lot is at stake if Tunisia’s nascent democratic experiment falters. It would further demoralize democracy activists and movements in the Arab world and embolden regional autocrats and illiberal populists who trash democracy as an inherently flawed system. The failure of democracy in Tunisia would also vindicate violent extremist movements who have attacked Ennahda and other political Islamists for naively putting too much faith in ballots instead of bullets.

What roles are regional actors playing in this crisis?

Some critics of Saied’s actions fear that outside powers have abetted his power grab. Ennahda supporters suspect that the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Egypt have played a role in urging Saied to seize power and sideline their movement. Both regimes are known for their visceral hostility to political Islamists, including Ennahda. The UAE, in particular, has been suspected of funding political figures and political parties opposed to the Islamists. Leaked documents allegedly originating in the UAE pointed to a deliberate strategy of political interference in Tunisia’s affairs. Influential television and social media figures close to the power structures in the UAE, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia have celebrated what they describe as Saied’s fatal blow to Islamists. This amplifies the fears of those who believe that the axis of Arab autocrats is determined to sabotage Tunisia’s fragile democracy. Saied’s visit to Cairo in April, in the midst of his escalating dispute with Ghannouchi, is also seen by some analysts as “a move aimed at cementing relations in the face of the Muslim Brotherhood.”

Supporters of Saied also see a foreign hand in the crisis, especially that of Qatar and its Al Jazeera network. When the network urged Tunisians to defend their revolution and democracy, plainclothes police stormed its bureau in the capital Tunis, expelled its staff and closed down the office.

Between these two camps, there is Algeria, which played a constructive role in stabilizing the post-Ben Ali political transition.

Flag raising ceremony at Tunisia’s naval academy. (Photo: Rais58)

The Tunisian military has been seen as increasingly professional and apolitical. How are they responding to this crisis?

This crisis has put the military in a bind. Since the onset of the Tunisian revolution, the military has admirably resisted being drawn into domestic political conflicts. With Saied’s power move, however, the military had to execute political orders, the constitutionality of which is widely contested. By surrounding himself with military and security officials during his announcements to seize power, the military, willingly or not, has been used as a symbol in a highly contentious political dispute. The subsequent dismissal of the Minister of Defense as well as the military’s interdiction of Speaker Rached Ghannouchi from entering Parliament have reinforced the fears of some Tunisians that Saied is seeking to draw the military into this political crisis in support of his interests.

What can domestic and international democratic actors do to help safeguard Tunisia’s democracy?

Tunisia has a vibrant civil society that has played a key role in keeping the peace in the country. Today, several influential civil society organizations are once again pleading for a road map with a detailed timetable. Influential Tunisian NGOs have warned against any illegitimate extension of the suspension of Parliament, stressing the need to respect the 30-day deadline mentioned in Article 80 of the Constitution. Tunisia’s Nobel prize-winning trade union, the Tunisian General Labor Union (UGTT), which has not denounced Saied’s steps, has also called on the president to stay within constitutional boundaries. UGTT officials also hope to replicate their 2013 successes when they helped broker a peace road map that averted a counterrevolution as occurred in Egypt that year or a descent into civil strife as was unfolding in Libya.

“It is important to continue urging, and pressuring, Saied to return Tunisia to its democratic path.”

International democratic actors can also play a critical role in resolving the current political crisis. It is important to continue urging, and pressuring, Saied to return Tunisia to its democratic path. It is equally critical that Tunisia’s partners begin to seriously help Tunisians climb out of their deep economic hole. So far, the fight against terrorism and the desire to stem migration have detracted attention from addressing Tunisia’s crushing debt crisis, an economy under duress, and rising despair and anger among the country’s legions of unemployed youth. To be sure, it is up to Tunisians themselves to resolve these socioeconomic issues. But without significant external economic assistance and political nudging, it is difficult to see how Tunisia’s democracy can survive in this time of dire need.

Additional Resources

- Carlotta Gall, “Why Tunisia’s Promise of Democracy Struggles to Bear Fruit,” New York Times, July 28, 2021.

- Riccardo Fabiani, “Tunisia’s Leap into the Unknown,” International Crisis Group, July 28, 2021.

- Sharan Grewal, “Kais Saied’s Power Grab in Tunisia,” Brookings, July 26, 2021.

- Anouar Boukhars, “Tunisia Crying Out for Change,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, September 27, 2019.

More on: Democratization Tunisia